Are the Military Services Prepared for Race-Neutral Admissions? Part II

17 January 2024 2024-04-13 18:47Are the Military Services Prepared for Race-Neutral Admissions? Part II

Are the Military Services Prepared for Race-Neutral Admissions? Part II

By Major Geoffrey Irving, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve

. . . . First, the Supreme Court required that any use of racial classification must have focused and measurable objectives. In other words, the government must state its compelling interests in a measurable way.

Second, the Supreme Court required that even if there is a compelling interest, the use of racial classifications cannot employ race in a negative manner (e.g., disadvantage any person because of their race) or involve racial stereotyping (e.g., assuming someone will have particular attributes because of their race alone.)

Third, and somewhat uniquely, the Supreme Court required the use of racial classification have a logical end point, after which racial classifications would no longer be necessary.

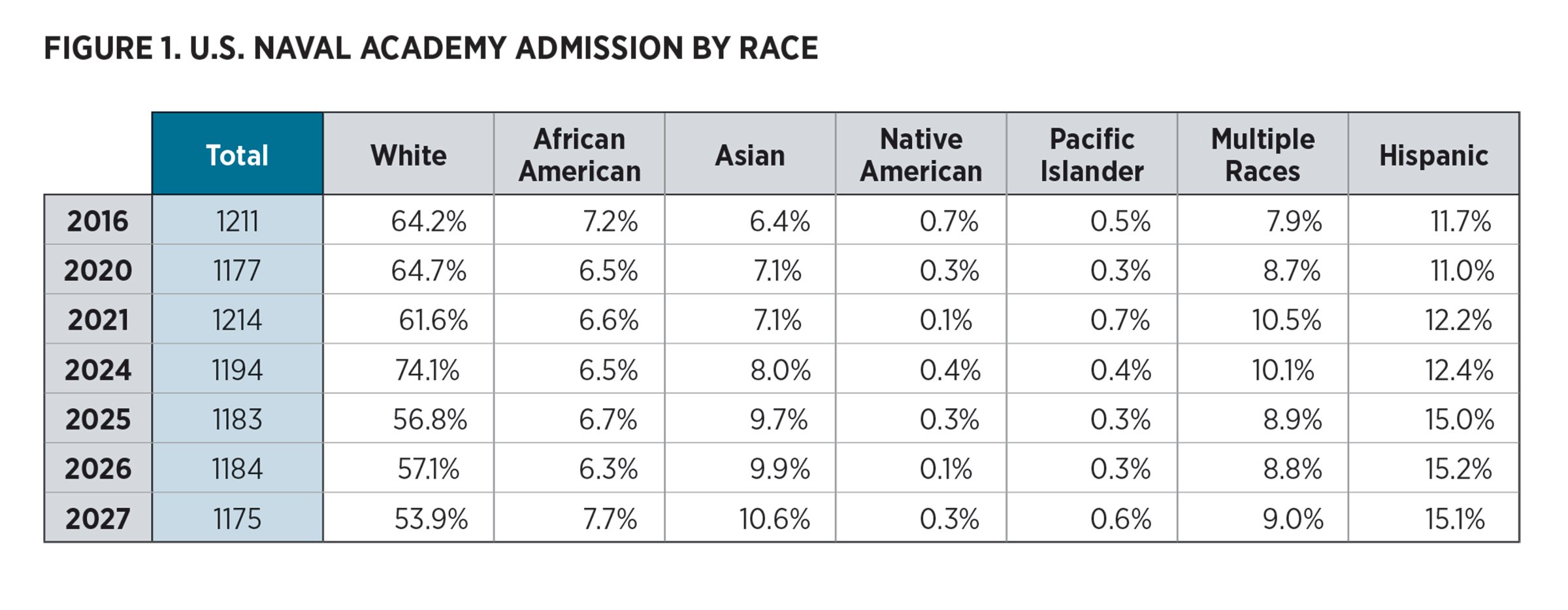

The Naval Academy uses race as a factor when admitting students. It does not use quotas, but rather uses race in a holistic manner. However, the Academy’s holistic consideration of race produces notably stable admission rates by race. See Figure 1.

To pass the SFFA v. Harvard test, the Naval Academy must show that the use of racial classification in admissions has focused and measurable objectives.

The objectives of racial classification in service academy admissions differs from those of civilian universities.

In a brief submitted to the Supreme Court, former Naval Academy superintendents, and other generals and admirals argued that racial classifications are necessary because the racial composition of the military officer corps needs to reflect the racial composition of its enlisted corps.

In another brief, they also argued that the military has a powerful interest in developing an officer corps that is prepared to lead a diverse force and that shares the racial diversity of the enlisted ranks.

Both interests are founded in the belief that equivalent racial composition among officer and enlisted populations are necessary to preserve unit cohesion and reduce racial tension.

Alternatively, this group has argued that race-conscious admissions and other selection practices makes the Navy more effective at accomplishing its mission.

Seeking to match the racial composition of the officer population to the enlisted population is a clear and measurable objective.

However, that objective is not clearly tied to a compelling government interest in either promoting trust between officer and enlisted member populations or to accomplishing the Navy’s mission.

Implying that trust between enlisted member and officer populations can only be achieved with racial parity invokes a stereotype that enlisted service members form opinions of their peers and officers primarily based on an assessment of race rather than in terms of character or competency.

Furthermore, the proposition of balancing the racial profiles of both populations implies that the Naval Academy will require the use of racial classifications in perpetuity.

Despite these weaknesses, the court may nonetheless give it a degree of deference as it often does to matters of national security.

However, even if the Naval Academy gets deference because of its proximity to matters of national security, it will have a difficult time showing that these racial classifications do not disadvantage applicants based on race or involve racial stereotyping.

In SFFA v. Harvard, the Supreme Court was clear that “college admissions are zero-sum.”

It clarified that, “a benefit provided to some applicants but not to others necessarily advantages the former group at the expense of the latter.”

Given this unequivocal statement, it will be hard to argue that race-conscious admissions that provide advantages to applicants of certain racial minorities do not disadvantage other applicants. . . . . (read more on US Naval Institute)

Related Posts

Search

CONTACT US

Recent Posts

Topics

RECOMMENDED LINKS

BE AWARE

More to Read

Navy OK with Drag Queen Ambassador’s Racy Instagram Content as Long as It’s ‘Unofficial’

Navy OK with Drag Queen Ambassador’s Racy Instagram Content as Long as It’s ‘Unofficial’ Marxist CRT at the US Naval Academy

Marxist CRT at the US Naval Academy What has become of the Marines?

What has become of the Marines? How Woke Politics are Endangering the U.S. Military

How Woke Politics are Endangering the U.S. Military USNA CRT/CP Smoking Gun

USNA CRT/CP Smoking Gun Navy Whistleblower Rips Leftist Woke Military in Retirement Speech

Navy Whistleblower Rips Leftist Woke Military in Retirement Speech Engineering Failures, Toxic Leadership Prevented US Ship From Deploying, Investigations Show

Engineering Failures, Toxic Leadership Prevented US Ship From Deploying, Investigations Show Woke Politics Are Endangering Our Military And Our Nation

Woke Politics Are Endangering Our Military And Our Nation When did we decide to abandon all we stand for as a nation?

When did we decide to abandon all we stand for as a nation? The Navy, the Marines, and Amphibious Ships

The Navy, the Marines, and Amphibious Ships